Eastern Hemlock Tree – The Silent Sentinel of the Forest

In the cool, shaded understories of North America’s eastern forests, there stands a quiet giant, graceful, enduring, and deeply intertwined with the ecosystems it supports. The Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), often overlooked for flashier flora, is a tree of elegance and ecological importance. With its drooping branches, feather-like needles, and a lifespan that can stretch over 800 years, the Eastern Hemlock is more than just a tree, it’s a living legacy.

A Tree of Subtle Beauty

Unlike the towering white pines or showy maples, the Eastern Hemlock exudes a gentle charm. Its needles are soft and flat, dark green on top with two pale stripes underneath, a telltale sign for identification. The cones are petite, only about the size of a nickel, but they’re perfectly formed, hanging like ornaments from its delicate branches.

Hemlocks prefer the cool, moist environments of ravines, stream banks, and north-facing slopes. In these shaded retreats, their dense canopies create microclimates that support a unique community of mosses, ferns, and cold-loving creatures.

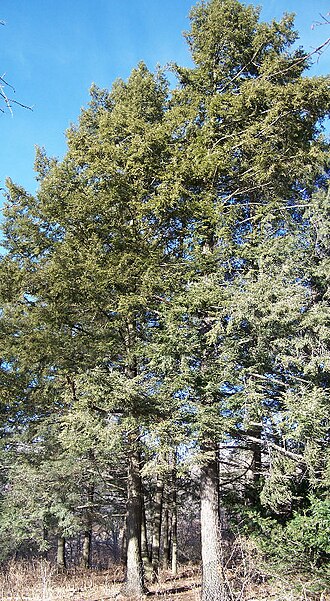

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) specimens at Morton Arboretum Creative Commons | Author: Bruce Marlin – Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tsuga_canadensis_morton.jpg

An Ecological Cornerstone

The Eastern Hemlock plays an essential role in the forest. Its thick foliage cools nearby streams, making it ideal habitat for native brook trout. Beneath its boughs, deer seek shelter in winter, and birds like the Blackburnian warbler nest high in its branches. Even fallen hemlocks, when left to decay, feed fungi, insects, and future forests.

But the hemlock’s quiet reign is under threat.

The Tiny Pest with a Big Impact

Enter the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, an aphid-like insect native to Asia that feeds on sap at the base of hemlock needles. These tiny invaders, recognizable by the white, cottony sacs they leave behind, have devastated Eastern Hemlock populations from Georgia to southern New England. Without intervention, an infested tree can die in less than a decade.

Scientists, conservationists, and citizen scientists are racing to save the species through biological controls, resistant seedlings, and forest management. In some parks and preserves, treatment efforts have slowed the decline, buying precious time for long-term solutions.

Shoot infested with hemlock woolly adelgid – Author: US Forest Service – Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tsuga_canadensis_adelges.jpg

Standing with the Hemlock

To walk through a hemlock grove is to step into a quieter, cooler world. There’s a kind of reverence in their shade, a sense of something ancient and enduring. As climate change and invasive species continue to challenge native ecosystems, protecting the Eastern Hemlock becomes not just an act of conservation, but of cultural and spiritual significance.

Stand of eastern hemlock and eastern white pine in Tiadaghton State Forest, Pennsylvania; note the hemlocks’ deeply fissured bark. – Creative Commons | Author: Nicholas A. Tonelli – Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Stand_of_Eastern_Hemlock_and_White_Pine_in_Tiadaghton_State_Forest,_Pennsylvania.jpg

Whether you’re a hiker, a naturalist, or someone who simply loves the woods, learning to recognize and appreciate this tree is a small but powerful step toward stewardship.

So next time you find yourself wandering through a dimly lit forest and you feel the temperature drop, look around. You might be standing beneath the watchful limbs of an Eastern Hemlock, the forest’s quiet guardian.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsuga_canadensis